History

Iron Man’s magic sparks marvel of a night for Orioles

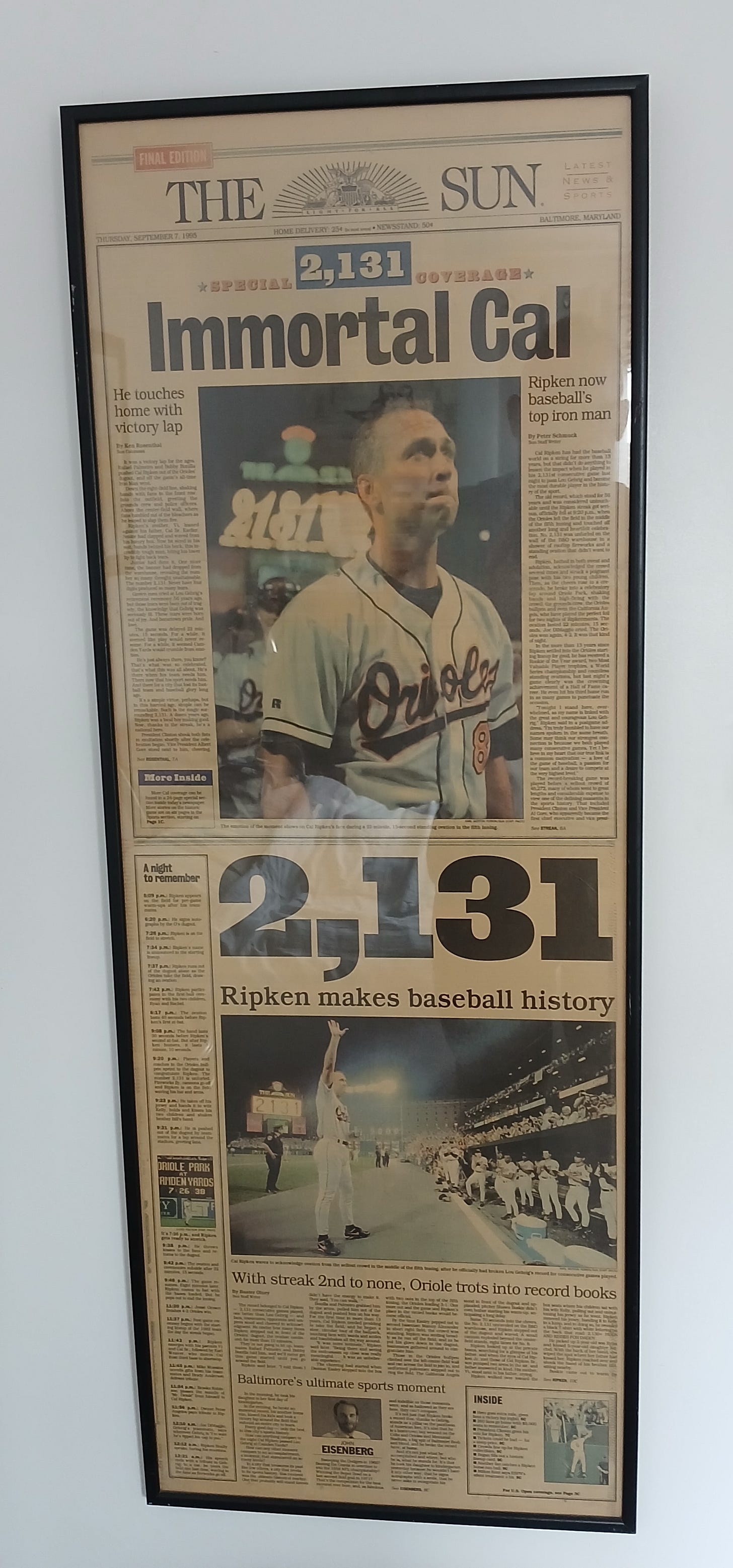

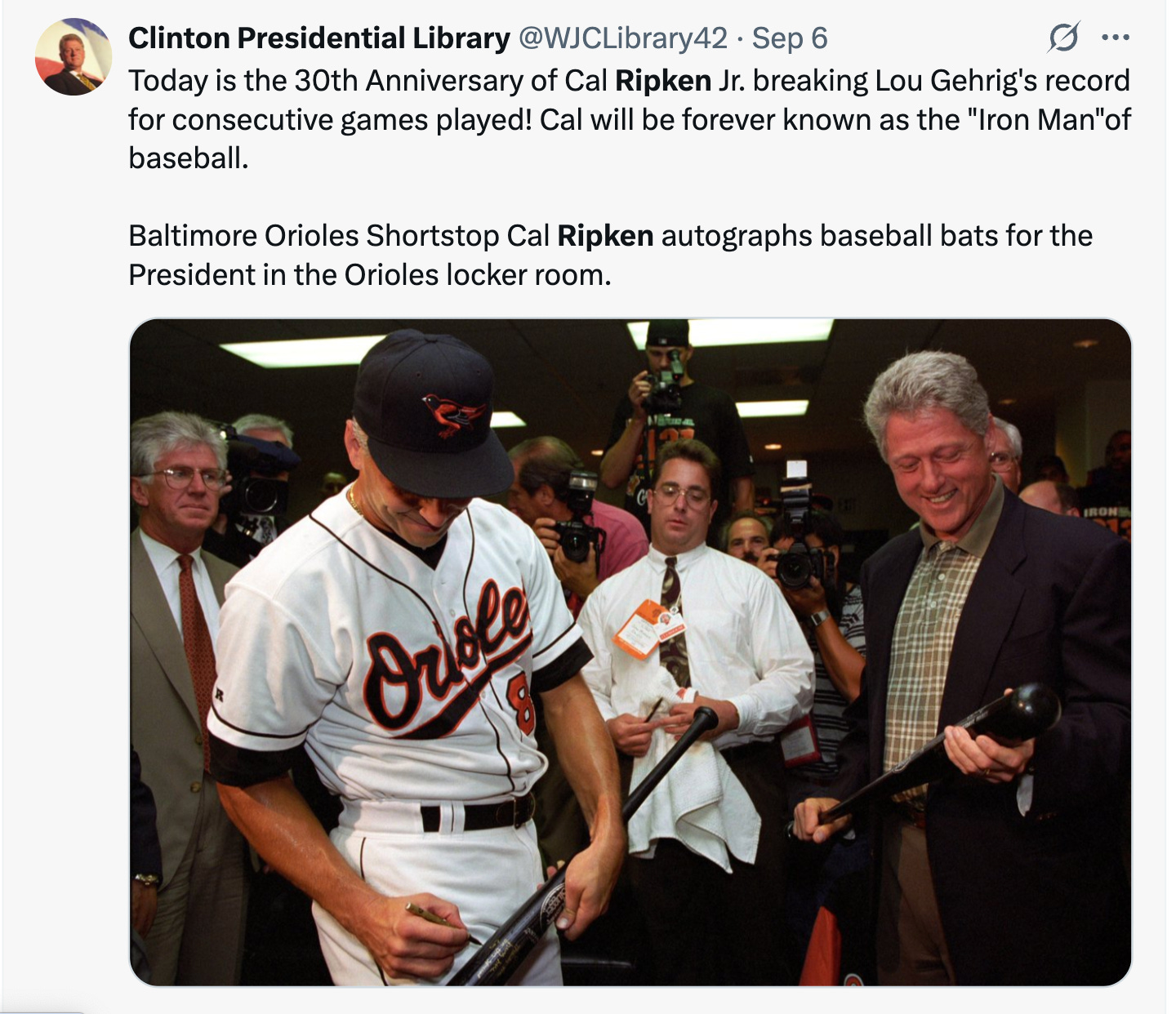

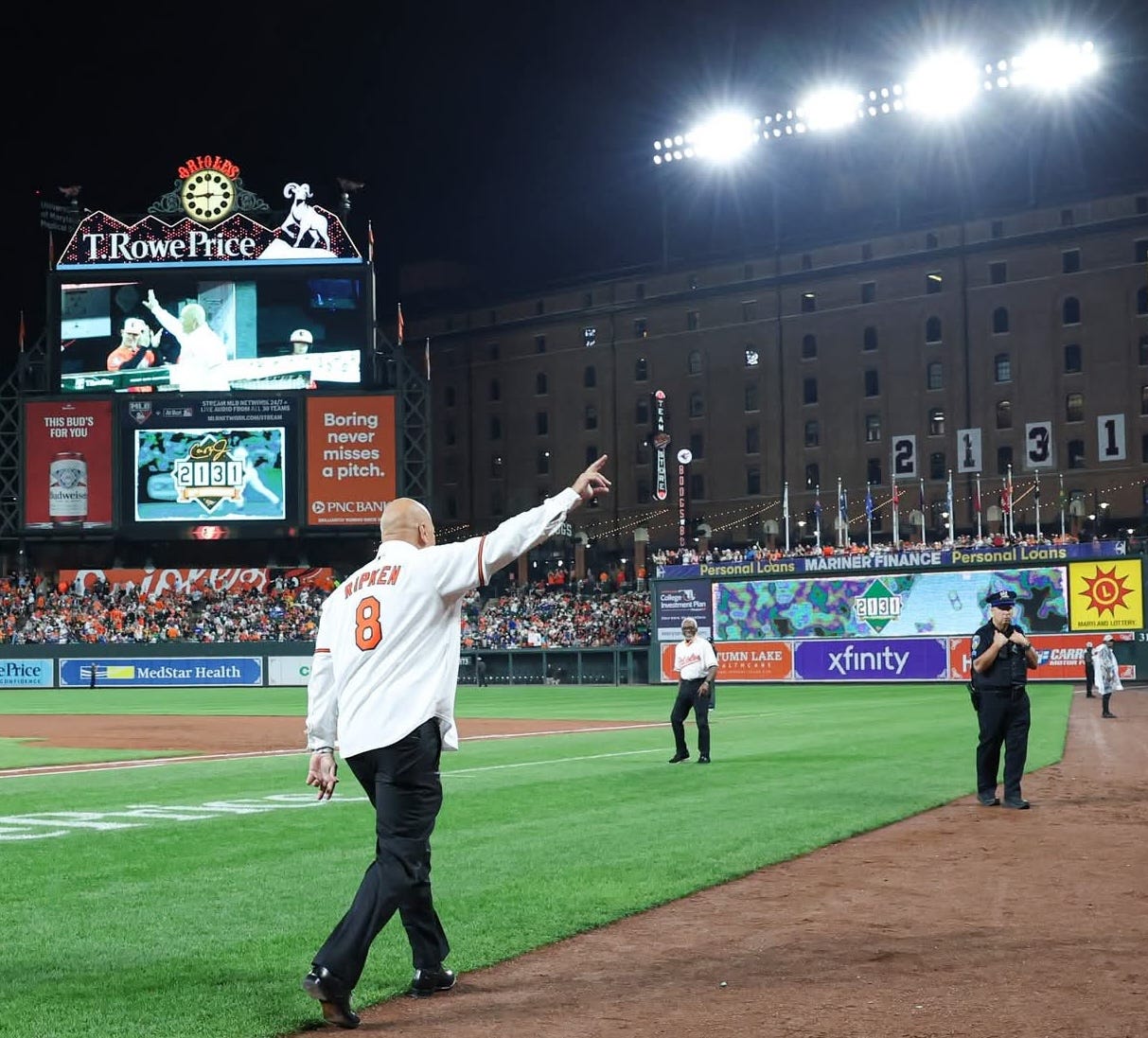

September 6, 1995 was described by sportswriter Tim Kurkjian as one of “the most powerful, inspirational and important nights in the game's history.”

Thirty years later, the Baltimore Orioles joyously celebrated their hometown legend then made some more history of their own.

In a stunning finale to Saturday’s game against the Los Angeles Dodgers, the O’s – who, lets face it, have not had much to cheer about this season – broke up Yoshinobu Yamamoto’s bid for a no-hitter with a two-out home run by Jackson Holliday (wearing Cal Ripken Sr’s number 7) before coming back for an unlikely 4-3 walk-off victory.

The Orioles are the first team in the expansion era (since 1961) to win a game after breaking up a no-hit bid when down to their final out.

As Jake Rill writes at MLB.com:

“Holliday became only the eighth player on record in AL/NL history to break up a no-hit bid with a two-out home run in the ninth – and the previous seven each had his team go on to lose.

“It was the fourth time in the expansion era (since 1961) the Orioles ended a no-hitter with two outs in the ninth or later. Holliday joined a group that includes teammate Gunnar Henderson (Sept. 13, 2024, at Detroit), Jim Traber (Sept. 30, 1988, at Toronto) and Davey Johnson (June 7, 1968, vs. the A’s).”

Johnson, who played for the O’s from 1965 to 1972 and later managed the team, passed away the day before, at the age of 82.

Baseball really is the best.

*

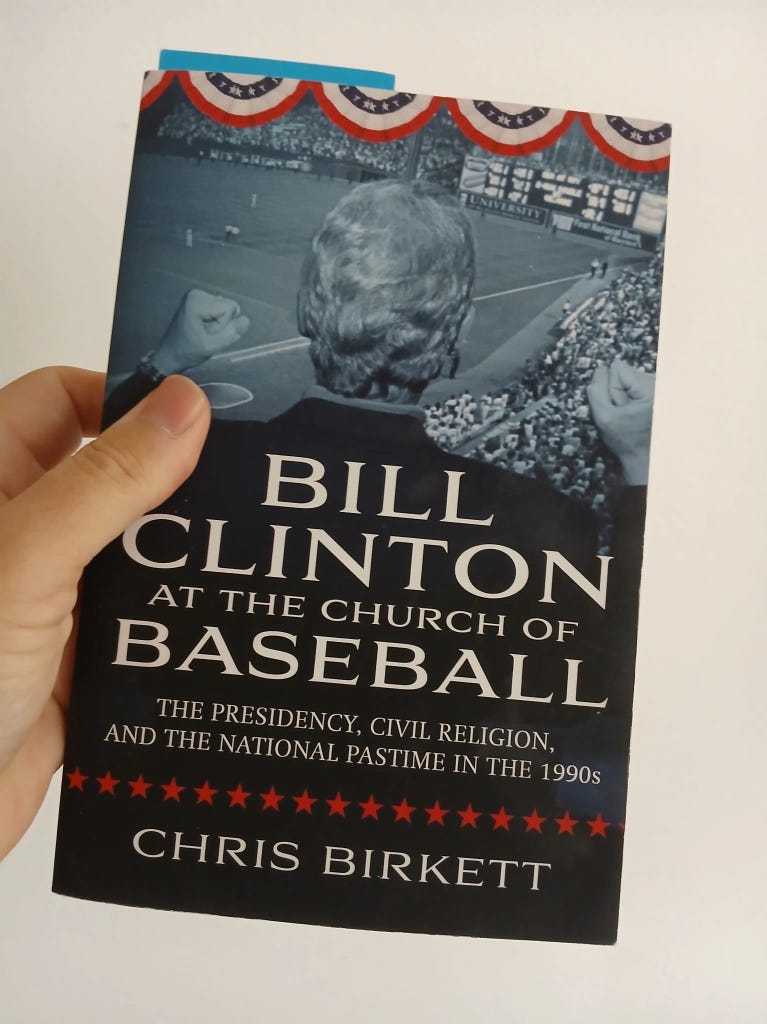

Among the thousands in attendance thirty years ago for Ripken’s history-making game was a BBC News journalist, Chris Birkett. He would later, as an historian, consider the significance of the night – from both a sporting and a broader, social and political perspective – in his excellent debut book, Bill Clinton at the Church of Baseball.

In a chapter entitled ‘Going to Work is as American as Baseball’ he writes:

“The interested parties in the propagation of Ripken’s narrative of work, duty and responsibility were multiple. Importantly, it was a story of mutual benefit to two connected industries: the multi-billion-dollar baseball industry, whose owners craved a heroic role model to recapture the strike-alienated fan base and reconnect them to the game’s supposedly wholesome past; and the media enterprises whose revenues relied on the popularity of its sports content for readers, viewers and advertisers. It resonated in the political arena too: public declarations of admiration for the universal qualities embodied by Ripken allowed politicians of all hues to appear above the partisan fray at a time of intense cultural conflict and noisy jeremiads of national decline. Finally, the uplifting Ripken story was of particular advantage to the President: Ripken’s potency as a cultural symbol, whose endurance embodied the American work ethic, aligned with Clinton’s promotion of a policy at the core of his domestic agenda – the transformation of the welfare system by ending benefit dependency and pushing people towards work. In embracing the story of Cal Ripken Jr’s steadfastness at work, Clinton was uniting two elements of America’s civil religion – baseball’s nostalgic representation of ideals of community and integrity and a belief system that associated the work ethic with self-fulfillment and personal independence.”

He goes on:

“With his small-town background, itinerant youth, blue-collar persona and one-club career, Ripken fulfilled a baseball creed that had existed since the mid-nineteeth century; that it was an indigenous sport, originating in the countryside, and that when brought to the cities, baseball imposed order and inculcated idealized American values of self-reliance, loyalty and community pride on a messy urban world.”

I’m particularly happy that Chris was able to do a Q&A with me this week of all weeks, where he talks more about the relationship between baseball and American politics, specifically through the Clinton presidency.

I hope you’ll read it here – A Journey Through The Fraying Of America.

*

Ballin’

Finally, I’ve never snagged a ball at a major league game. Never even come close. The only ball I have from an actual game was tossed to me by one of the outfielders between innings at the single-A Charleston River Dogs about 20 years ago, and that was only because I knew his name and called to him.

I also just missed catching a foul ball at a spring training game in Clearwater a few years before that, when I twisted my ankle jumping for a ball that sailed over my head and landed at the feet of a guy a couple of rows back. He was on his phone and nonchalantly said to whoever he was talking to: “Hey, I got a ball!”

So in five decades of going to baseball, that’s as close as I’ve come. But one thing I always do, as force of habit, anytime I take a seat in any stadium, is look around for little kids sitting nearby, so that in the rare possibility that a ball heads my way, I’d know who to give it to.

That’s why incidents like the one that received way too much exposure this week involving Phillies fans at their team’s game in Miami always sit badly. But thanks to social media, we’ll likely just see more of them.

This, on the other hand, is still how it should be done.

***

As always, thanks for reading. I aim to write a baseball-related post midweek and a politics wrap at weekends.

Usually one is more sane than the other, particularly at our increasingly surreal moment.

You can find a full States of Play archive here.

*